(1.a) Economics—an evolving definition

(1.b) My definition of economics

(1.c) Examples of self and social harmony

(Chapter 1) The essence of economics

(1.a) Economics—an evolving definition

The ancient Greeks used a term Oikonomia, which combined the word oikos, meaning household or estate, and nemein, which means management. It can be thought of as prudent management of a household, but household here really means something akin to an estate, where weath is generated by business and supports a group of closely related people, usually family. Many writings on Oikonomia circulated in the Greco-Roman world, by famous men such as Xenophon and Aristotle, but they were not describing how to run a business, but how to run a family. For example, discussions of managing estates would often be separated as (a) managing slaves and servants (b) managing the wife (c) managing the children and (d) managing property. The goal of proper management wasn’t just to make money, but to preserve important traditions, to behave ethically, and the pursuit of a noble life. [L1]

Fast forward roughly two thousand millenia into the 18th century and intellectuals began to study and write about the management of a nation’s politics, especially in regards to laws about business, trade, and taxation. Because they were viewing the governing of a nation much like the management of an estate, borrowing the Greek term Oikonomia they called this study political economy, but they referred to themselves (and were the first to do so) as Les Économistes—that is, economists. These men strived to be read by other intellectuals and to be appointed as advisors to monarchs. While they approached business, trade, and taxation with the mind–set of a scientist, they were very much political players.

When Louis XV was King of France in the mid–eighteenth century he once asked an intellectual named Quesnay what he would do if he were king. Quesnay answered, “Nothing”. “Who, then, would govern?” asked the King. Quesnay replied, “The laws,” and the ‘laws’ he referred to were those natural to man as he conducted trade and business, and those laws revealed as markets government supply and demand.[D1]

The King did indeed take his advice, and allowed market prices to fluctuate without government interference. Before, there had been restrictions on the amount of grain that could be transported and sold to different regions in France, with additional restrictions on exporting grain out of the country. This included both physical restrictions on amounts that could be transported as well as tolls on grain as it crossed from one region to another. These restrictions and tolls were then abolished, and it worked well at first. The price of bread fell, which was a gift to the many poor but then a bad harvest in 1765 created a famine. The poor stole food from pig troughts, and in one parish of only 2,200 a total of 1,800 were found begging for bread. Although the shortage of grain was due to a bad harvest, not policy, many noticed that while the poor were starving many of those who owned grain were exporting it to other countries. You see, markets do not serve those who have no money, and the unrest caused by the experiment forced Louis XV to reverse course and reinstate the restrictions on grain trading [D1]. In this class we will learn about the abundance of wealth free markets can produce, but if the sharing of that abundance is not perceived just, those generous markets may not be politically feasible. It would take some time before people learned that society only embraces markets if those markets serve everyone.

These french economists forged a whole new way of looking at society, and the intellectual tools they developed were then taken up by British philosophers. Economics as we know it today is usually said to have begun with the 1776 publication of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nation. Though much of the book echos the ideas of earlier French economists, he offerred new insights into exactly where wealth is derived. Smith observed that much of our wealth comes from the ability of firms to be more efficient through specialization, which they then trade in markets. The basic idea is that:

- For a nation to produce lots of goods per person, each individual person must be productive

- An individual becomes more productive by specializing, allowing the division–of–labor and honing of skills

- Specialization only makes sense if different people specialize in different things, else a nation would have large amounts of only a few goods

- But by firms, and nations, trading what they do produce for what they do not, everyone can consume large amounts of many goods.

The book of course is about more than those simple arguments. It is also a large, eloquently written treatise. Perhaps most importantly, modern economists can find very little wrong with it, and if we have to identify a single founder of economics, Adam Smith is better than any other. Smith was referred to by others, and himself, however, as a moral philosopher. It is for this reason that Smith is considered the twentieth most influential person of the second millenium.

(Interestingly, though the documentary is largely accurate, there is no documented case where Smith used the term laissez–faire).

As the nineteenth century unfurled and opened into the twentieth, science made considerable progress, so much so that researchers became specialized. Natural philosophers became physicists, chemists, or biologists, and moral philosophers became political scientists, sociologists, and ... economists. Before, those who studied political economy wanted to be seen less as political players and more like objective scientists, and it was thought that dropping the word ‘political’ would help make this happen. Those who studied economic issues like business, trade, and taxation became less directly involved in politics and expanded their interests beyond the management of a nation, and so political economy became economics.

Economics defined

The definition of economics I heard most often in school was that it was the study of the allocation of scarce resources. That doesn’t mean much without an example, so consider the example of natural gas in 1985 Uzbekistan, which at this time was part of the Communist Bloc. The country had large reserves of natural gas. The US has large gas reserves also, and like Uzbekistan, uses it for many reasons, including fuel for stoves. Yet there was a curious difference in how Uzbekistan managed its natural gas reserves—how they “allocated” their scarce natural gas (although the reserves were vast they were limited and so economists still say they are scarce). In the US the gas was owned as property by companies and sold to consumers. In Uzbekistan it was owned by the government and given to its citizens for free. Those are certainly different approaches to managing the gas reserves, but the really curious part is how the people managed their stoves. In the US they only ran gas when they needed it to cook. In Uzbekistan many people kept the stoves burning all day, every day, regardless of whether anyone was cooking.

It is obvious why people in the US didn’t waste gas: because it would cost them money. Yet, even if the gas was free in Uzbekistan, why would people be so deliberately wasteful? It turns out they had a good reason, and the reason had to do with the matches to light the stoves. In the US it was provided by the private sector, so as long as one had a little money they could easily buy them. Matches were provided by the government in Uzbekistan, though, and because people could not profit by producing them there was little reason to produce much. Few matches were produced, and so matches were rationed. With little matches to go around households knew that if they wanted to be able to light their stoves to cook they could not always count on having matches, so they had to leave their stoves burning continuously.

Normative economics—study of how an economy should behave; of what ought to be

There are two perspectives of this example. One uses a positive economics perspective, where we study what actually happens in both the US and Uzbekistan, without judgment, and without saying what should be. Here the economist would describe the two different systems used to allocate natural gas to its citizens, why the two countries adopted different methods, and the facts about the consequences.

Yet science should always be used for the good of people, so economists would be remiss if they simply studied the world without any attempt to improve it. When looking at the example from a normative economics perspective might say the US system is better for its people and that Uzbekistan “ought” to adopt a market–based approach to managing its natural gas supplies. By providing natural gas for free but doing a poor job of providing matches Uzbekistan ultimately wasted enormous amounts of natural gas. Although free to the citizens at the time the gas is not really free, for using it today denies the ability of future generations to use it. What Uzbekistan did was aking to taking an enormous deposit of natural gas and flaring it all off—simply burning it and getting no use of it whatsoever. Though giving the gas away for free might sound nice, ultimately, the US system of relying on the private sector ensures that the vast majority of the gas is used to benefit people.

This is why nothing should be given away for free, economists believe. It isn’t because we do not want people to get free things, we just believe there is nothing that is really free. As mentioned above, giving free natural gas to one person means another person cannot have it, and it does not mean that someone did not pay for the gas to be extracted and transported. One of the more famous definitions of economics is given by Lionel Robbins, seen here. The “given ends” refers to the different uses of natural gas and the “scarce means” refers to the fact that the gas is limited in nature. When natural gas is wasted by being burnt for no purpose is prevents the gas from serving people in other ways: like generating electricity for lighting, or powering automobiles, or heating schools, and the like.

These two definitions are useful but hardly inspiring, and economics has the reputation of being a rather bland science. It is often referred to as “the dismal science”, a phrase coined by the famous Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle. His disappointment with economics was that it did not provide the defense of slavery that he wanted. He wanted a science that would justify keeping people enslaved, but economics seemed to suggest that it would be better to free them. So for the same reasons Carlyle thought economics dismal we today should find it inspiring [D2].

I would like to offer a different definition, one that better captures the noble goal to which economics aspires and the aspect of social order it focuses on most.

(1.b) My definition of economics

- people interact with strangers and acquaintances

- through commerce and government

- to create a more prosperous and meaningful life,

- with a particular interest in making self-interest and social-interest harmonious

(1.b.1) people interact with strangers and acquaintances

Money rarely changes hands between intimates. Lovers don’t buy and sell dates from one another, and spouses don’t agree in advance how their income will be shared. Mothers are loved by children for the love they receive, not by the size of their allowance. We do favors for friends because we care for them, not in expectation that they will soon return the favor (if we are real friends, that is).

Our intimates are few compared to the number of strangers and acquaintances we pass each day. Yet most of the food you eat is provided by strangers! When strangers meet, you can bet that money will change hands. The potatoes grown to make your french fries were not produced out of a sincere concern for your happiness, but to make the farmer money. We don’t buy french fries at McDonalds because we know and love the farmer; we buy them because we French Fries are tasty. The people who defend us in court do it mostly for the money. Bailey Norwood only teaches this class because it is his job (though he does love his job). Even in places where camaraderie between strangers is at its most intense—think college football—lots of money are being paid and received. We all love Mike Gundy for what he has done for our football program, and we know he loves OSU, but he is not family. He is our champion, but he is paid handsomely.

When strangers interact, money changes hands, and an economist is watching.

(1.b.2) through commerce and government

Although money does pass between father and child, friend and friend, most exchanges of money takes place in the marketplace (commerce) and government. We go so far as to recommend that one “not mix business with pleasure.” This separation between intimates and the marketplace seems both deliberate and desired. Roughy a third of all the money Americans make are paid to governments through taxes, so economists are keen to make sure this money is well-spent. Consider for a moment where most of a household’s after-tax income goes to: the home. It is not unusual for one to purchase a house at a price over twice her annual income. She borrows this money and then steadily pay it back over, say, twenty years. Who do they borrow the money from? Their parents? Rarely. Friends? Almost never. Strangers, who work at a bank? Almost exclusively. There are strangers who are willing to give us a huge sum of money because they have confidence that it will make them money. Why do they trust us? Aren’t they scared we will take the money and neglect to pay them back? No, because laws are written such that if we do not pay back the loan the bank can take ownership of the house and sell it. If we refuse the leave the house, the police will make us. Laws about property and contracts are the prime reason it is so easy for us to obtain a mortgage.

Commerce just describes exchanges between buyers and sellers in a marketplace, but you can find markets in both utopias and dystopias. A type of commerce and social order that benefits the common good requires good governance, so you cannot study markets as isolated from laws and politics. .

What economists rarely study is how customs and culture change over time. That is largely the domain of sociologists and anthropologists. Economists are paying more and more attention to culture, but the bulk of what is called economic theory concerns commerce and government.

(1.b.3) to create a more prosperous and meaningful life

What does it mean to be prosperous? Making a lot of money is a big part of it, because with money people can buy many of the things they value—but I didn’t need to tell you that, did I? It is thus not surprising that economics was born with the publication of a book titled The Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith. Economists devout much resources to learning how to help nations out of a recession and to help developing nations gain in wealth. It would be a mistake, though, to believe that economists definition of “wealth” concerns only those things that are bought in the marketplace.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson in essay Wealth

As chicken manure leaves the fields and enters Oklahoma streams, rivers, and lakes, economists say that citizens are less wealthy, even if the number of their dollar bills does not decline. Many people value environmental purity, and even if they never visit a lake but are “merely sad” at learning of the pollution, an economist will say that is equivalent to a reduction in wealth. Some people even become happier as they give some of their money to other people. We know that people give time to charity, fund charitable projects, and enter monasteries because there are some things more important than buying more toys. The fate of lottery winners is not encouraging to those who believe money buys happiness.

When I was first taught economics it was described as the study of the allocation of scarce resources. How humans deal with their unlimited wants in the presence of limited resources. Indeed, economists usually describe people as wanting more “stuff” regardless of how much they already have. Our desires are never satisfied. Or are they? This is a matter of semantics. We all know there are monks who renounce all possessions, so at first glance it may seem that some people’s preferences can be satiated. What if this monk could give away, for free, food to the hungry? Or what if he could magically provide houses for the homeless, comfort for the lonely, medicine for the sick? Surely, he would do so, so this monk does want more “stuff”, he just wants other people to be the ones to enjoy it, and then he gets happiness from their joy.

Humans are never fully satisfied with their wealth, but of course we want other things like close friends and to see our generosity benefit the world. The Onion once did a farce on our unsatiated desires, and though it was meant to be funny, it speaks worlds about our true desires.

What is a “meaningful life”? It varies across people, and when one becomes an economist it is like taking a vow to avoid judging the tastes of other people. If one person is happier renouncing all possessions and becoming a Franciscan monk, while another is happier spending all their time accumulating money and boasting of their riches, we respect their choices and wish them the best. If someone is happier eating large amounts of fatty food than enjoying a long and healthy life, that is their choice and the economist views this little different than preferring vanilla over chocolate ice cream. There are limits to this, of course. People will probably be happier in the long-run if they stop doing heroine today instead of next year, and sometimes people do not have the proper information to make an informed choice. The point is that we try as hard as possible not to impose our preferences onto other people, so long as their actions do not impact the happiness of others.

Oklahoma State University is fortunate to have the most famous agricultural economist in the world: Jayson Lusk. In his book The Food Police Lusk describes why he believes organic foods provide no real benefit to consumers. This is information he believes is backed by science and important, and he works hard to communicate this information to the public. At the same time he has no desire to force people not to buy organic food, and he would never support government policies that would impede with consumer freedom to buy organic food or farmer freedom to grow and sell organic food. This is why he is a helpful economist: he wants to inform the public, not coerce them.

(1.b.4) with a particular interest in making self-interest and social-interest harmonious

Humans can be very altruistic. We are an ultra-social animal, and cannot prosper without each other. At the same time we are individuals who want the freedom to work for their own benefit. Yes, we live in herds, like armies of ants or a hive of bees, but we are slaves to no queen. As individuals we only consistently work hard where it benefits us directly, but as a society if we profit at the expense of others we destroy each other. It is for this reason that a society only really prospers if people are paid for their work, and the people who pay them benefit from their work also. It is for this reason that economists are captivated by the notion that it is relatively easy to design an economy where people work for their own self-benefit and for the benefit of others at the same time. After all, every time a buyer and seller make an exchange they are both made better off. Otherwise the exchange would not have taken place. In this way, strangers can perhaps benefit each other more than friends and family!

Consider a non-agricultural example. Our financial system is such that a large bank can take great risks, and if the risks results in large profits they get to keep it all, but if they incur large losses the government—the taxpayers, that is—bails them out. This is an undesirable system because it results in excessive risk taking, where small profits are funneled to a few people but large costs are imposed on society. The bankers are only being rational. The incentives are such that to not take such risks would to be to leave money on the table. Although it is rational for the bankers to take these risks, it is not rational for citizens to encourage this by continually bailing them out. Such a system takes an economy from one financial crisis to another.

(1.c) Examples of self and social harmony

(1.c.1) Shipping prisoners

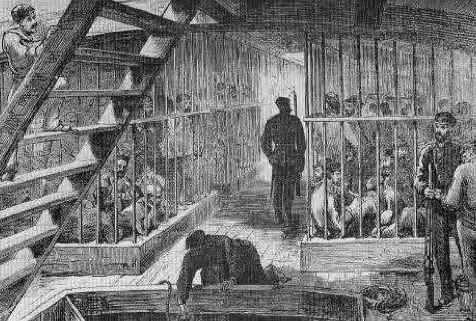

Britain used to ship some of its prisoners to Australia, and ships were initially paid per person they transport. People can be cruel, and it costs money to ship prisoners humanely, so it is unfortunate but not surprising to learn that many ship captains cared for their prisoners so poorly that few arrived in Australia alive. The Britain government and public was shocked to discover this fact, and decided that what was in the ship captain’s self-interest was not in Britain’s self-interest.(K1)

Designing a new system where self-interest and social-interest were aligned was easy. Instead of paying ship captain a specific amount for each prisoner transported regardless of whether they arrived alive, they paid each captain a specific price for each prisoner that arrived alive. This new system apparently fixed the problem, as ship captains began to care for their prisoners much better, regardless of whether the captains were naturally benevolent or malevolent people.

(1.c.2) Managing fish populations

(1.d) Motivation for millennials

Even if one does not care to understand how people interact with strangers and acquaintances through commerce and government to create a more prosperous and meaningful life, with a particular interest in making self-interest and social-interest harmonious, the fact is that the world does consider it a worthy subject. An educated person is expected to understand basic economics.

So integrated is economics with modern life that sometimes one must understand it just to understand jokes like the following on television!

References

[A1] A&E Documentary. 1999. Biography of the Millennium: 100 People -1000 years.

[D1] Durant, Will and Ariel Durant. 1967. Rousseau and Revolution. Page 76.

[D2] Dixon, Robert. The Origin of the Term "Dismal Science" to Describe Economics Accessed December 27, 2016 at http://www.krannert.purdue.edu/faculty/smartin/ioep/dismal.pdf.

(K1) Kestenbaum, David. September 10, 2010. “Pop Quiz: How Do You Stop Sea Captains From Killing Their Passengers?” Planet Money [podcast]. Accessed December 16, 2014 at http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2010/09/09/129757852/pop-quiz-how-do-you-stop-sea-captains-from-killing-their-passengers.

[L1] Lesham, Dotan. 2016. “What Did the Ancient Greeks Mean by Oikonomia?” Journal of Economic Perspective. 30(1):225-231.

(R1) Radiolab [podcast]. December 12, 2014. “Buttons Not Buttons.”

(S1) Seabright, Paul. 2004. The Company of Strangers. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ.