(2.a) Six figures showing human progress

(2.b) How to feed a large nation

(2.b.1) Engineering: Labor saving technologies

(2.b.2) Political Economy: Specialization and trade

(2.b.3) Political Economy: Property rights and flexible markets

(2.b.4) Political Economy: Decentralized decision-making

(2.b.5) Political Economy: Respect for honest profit–making

(2.b.6) Political Economy: A sincere sense of humanity

(2.b.7) Political Economy: Protection of natural resources

(2.c) Consensus on the Great Enrichment

(Chapter 2) The Harvest of the Great Enrichment

(2.a) Six items on human progress

Figure 2—Some nations got richer earlier

Quotation 1—Wealth creation needs food

Figure 3—Population up, price of food down

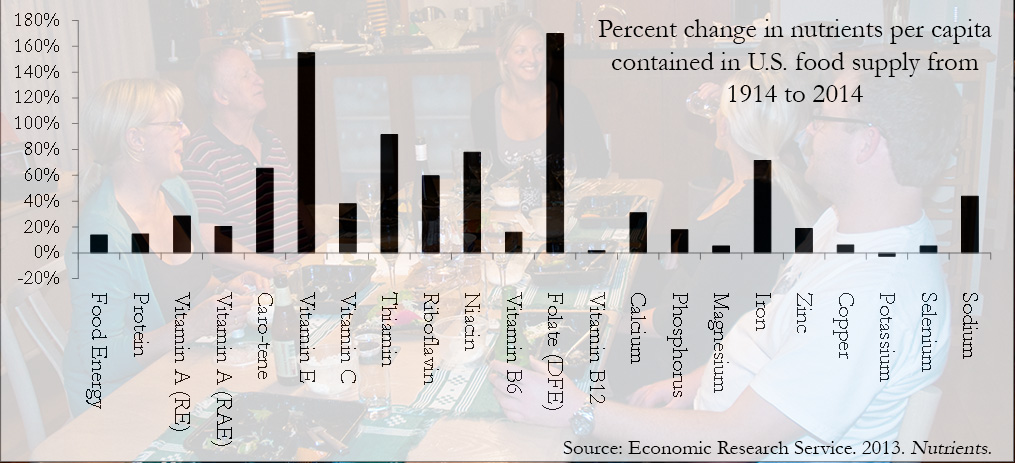

Figure 4—More food means more nutrients

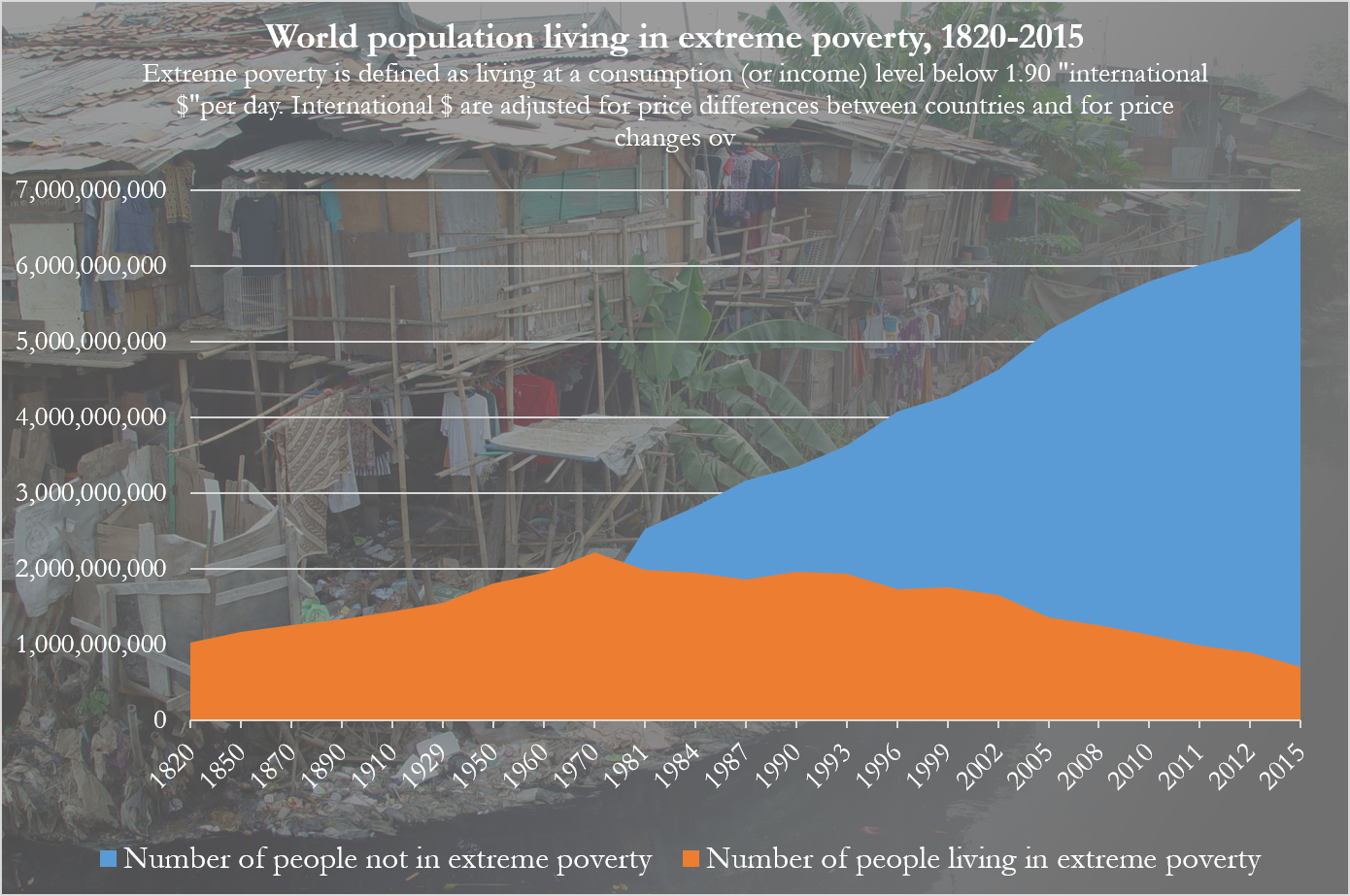

Figure 5—More happy people, less unhappy people

(2.b) HOW TO FEED A NATION

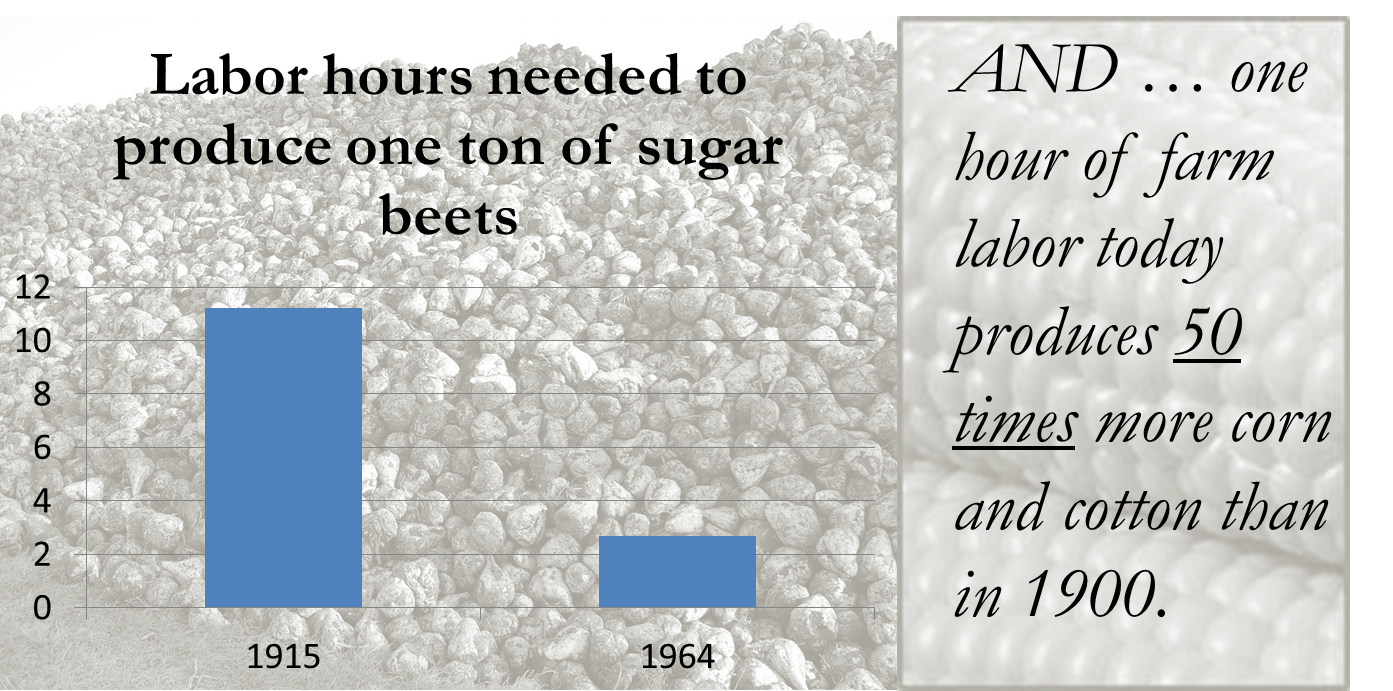

(2.b.1) Engineering: Labor saving technologies

Two Athenian tales

(2.b.1) Engineering: Labor saving technologies

Two Athenian tales

The Athenian problem

There was no political problem in Athens causing such suffering. The problem was technological. They simply did not have the tools and knowledge necessary to feed its people. Their effective democracy allowed them to feed their people better than most nations in a similar situation.

It is obvious that we can easier feed the world today with our modern technologies than it was for the ancient world to feed itself. They plowed the ground with slow oxen; we plow with large, powerful tractors. The ancient world had to plow the ground to produce much of their crops, and this leads to soil erosion, whereas with modern pesticides we can feed ourselves without hardly ever scratching the soil’s surface. The ancient world could only protect themselves from insects and disease by being wise about the crops they plant and using a few sources of ’natural“ insecticides like cow urine or pesticides like sulfur. Today we have synthetic pesticides that are more effective and often less toxic than their natural counterparts. It was hard for farmers thousands of years ago to breed better plants and animals, yet today we can use technologies like crispr to edit an organism’s genetics directly.

The advantage of modern farming technologies is not that they allow us to produce more food on a per acre basis. It is easy to produce large amounts of food from a single acre using even ancient farming methods. As long as you are willing to import large amounts of compost, employ irrigation, and rely extensivly on human labor an organic garden can produce more food per acre than possible on the most mechanized conventional farm. The problem resides in the large amount of human labor required. This is why organic food is more expensive, even though organic farms can be very productive. That organic garden may produce a lot of food on a per‘acre basis, but it produces little on a per labor hour basis. The reason we produce so much food per person today despite the fact that people work less than in the past is that the little labor we do devote to farm is very productive, producing enormous amounts of food. And because that agricultural labor is so productive we need only less than 2% of the population to work as farmers. The remaining 98% can take other jobs, like the health care center, so that we do not have to experience the high infant morality rates as our Athenian ancestor [G1].

Today’s technology is available to any nation that is willing to accept it, yet much of the world still has trouble feeding itself. Why? Because feeding a nation requires so much more than technology available. People must have to have the ability and incentive to adopt them in the first place, and to use them for the felicity of its people. To do this requires a certain political economy, which means today the obstacle to overcoming hunger is not an engineering obstacle but one of an economic and political nature.

(2.b.2 – 2.b.7) Political Economy

When psychologists set about measuring the impact of nature versus nurture they usually study identical twins. If identical twins raised in different households behave differently, that is an indication that the environment is more important than genetics. Likewise, we can study the effect of economic systems by taking a homogeneous region, splitting it in half, and installing one economic system in one half and a different system in the other.

The failures of Communist economic policy had the most tragic consequences in agriculture, the basis of the economy of nearly all countries subjected to Communist rule. The confiscation of private property in land and the collectivization that ensued disrupted traditional rural routines, causing famines of unprecedented dimensions. This happened in the Soviet Union, China, Cambodia, Ethiopia, and North Korea; in each country millions died from man-made starvation. In Communist North Korea as late as the 1990s, a large proportion of children suffered from physical disabilities caused by malnutrition; in the second half of the 1990s, up to 2 million people are estimated to have died of starvation there. Its infant mortality rate is 88 per 1,000 live births, compared to South Korea’s 8, and the life expectancy for males is 48.9 years, compared to South Korea’s 70.4. The GDP per capita in the north is $900; in the south, $13,700.

—Pipes, Richard. 2001. Communism: A History. Modern Library.

This picture shows the results of one of the largest experiments ever conducted. A single nation with a similar climate and culture in both the southern and northern part of the country were split in half after the Korean War. The northern half became a communist state ruled by an autocrat. The southern half became a capitalistic, representative democracy. Both countries have access to the same store of agricultural knowledge, the same agricultural technologies, and the same countries ready to befriend them and help them develop their agricultural sector.

Yet, as you can see from the picture, the capitalistic half is thriving, its brightly illuminated cities a symbol of its vibrant economic activity and wealth. The northern half seems basically dead, and indeed, death is something all too familiar in North Korea. In the latter half of the twentieth century North Korea confiscated all private property and made it the possession of the government. It no longer allowed people the freedom to choose their occupation, but forced them to work on government farms and government factories. It made trade illegal. Simply wanting to sell one‘s labor to buy some food became a crime.

The world would love to offer North Korea humanitarian aid and to help it develop its agricultural sector to produce food efficiently. The scientific knowledge, the technological innovation, it is waiting for North Korea to take, and for free.

We all know why North Korea won’t accept our charity. Because to farm as Americans farm requires American freedom: it requires private property and free markets (free markets meaning individuals are free to sell whatever goods they like at whatever price they can negotiate, with minimum interference from the government or individuals who wield power through force). American farmers are incredibly productive because of the scientific technologies available and their freedom to use the technologies however they like. Its citizens are of little concern to North Korean leaders though. They only care about power. Fearful it will lose its iron grip on its people, it would rather send its people into a famine every ten years than risk losing political power.

North Korea is the opposite of ancient Athens. If the political situation was better they could easily grow enough food. North Korea rejects everything American, because one way it maintains power is by depicting America as an aggressive enemy who is anxious to invade. Well, it doesn’t reject everything American. It accepts Dennis Rodman. It also allows its people to read and watch Gone With the Wind, because it hopes its citizens, during times of hunger, will be inspired by these famous lines of Scarlett O’Hara [S2].

But think ... why was Scarlett O’Hara hungry. Was it because the soils of her estate are infertile? No. Was it because of a recent drought? No. Was it because the South was overpopulated? No. Why, then? Because of a political problem: the Civil War. If North Koreans identify with this scene I suspect it is not just their experience with hunger, but a government hell-bent on the destruction of others to maintain the power of a few.

(2.b.2) Specialization and trade

Humans evolved to be social animals, living in groups to survive. Isolated in the wild results in almost–certain death. In groups with other humans, we conquer the world. One of key reasons for living in large groups is so that we increase our wealth through specialization and trade. Humans are social animals. We have to be. Alone in the wild we are most vulnerable of animals, but in groups we conquer the world. Our wealth, including our great abundance of food, results from each person honing their skills and become productive in a few things, then trading their surplus for things produced by other people. Think for a moment about all the things you consume in a day, from your smartphone to your food. Then count all the things you consume that someone else produces. This will even be true when you are a full–time worker. Most everything you have comes from trade, and you are able to get them because you have something to trade.

Imagine how hard it would be for you to actually produce all the things you consume in a day, including your car, computer, home, food, musical instruments, and the like. You could spend a lifetime learning how to do it, but you would only actually be able to learn how to make a few of those things. It is impossible to become efficient at producing everything you need. To be efficient at anything you need to specialize, taking the time to hone your skills, and not wasting time by moving from producing one good to producing another.

Specialization presents a problem, because if you produce only a few goods or services that means most of what you need in life must come from other people. This is why trade is essential for specialization, because it lets you trade the few goods you produce with other people—other people who specialize in producing other things—for all the other things you want and need in life.

You are fortunate to be born in a time and country that provides you with a higher standard of living than a king during the Middle Ages. This is possible not just because our technologies make labor incredibly productive, but because specialization and trade amplifies the benefits of those technologies.

Specialization and trade makes society a positive–sum game, which means [almost] everyone benefit at the same time. It is tempting to think of business as a zero–sum game, where one person’s gain is another person’s loss. While that may be true for bets it is not true for business. Bill Gates made large profits when we purchased his software, but we didn’t lose from the transaction. We purchased the software because it benefits us—otherwise we would not have purchased it in the first place. Gates was better off, and we were better off—that’s a positive–sum game.

Without trade with others we are resigned to life that is cruel, brutish, and short. With trade, we have Netflix, junk food, unnecessarily large cars, and spend our time killing wild animals not because we need the meat because we simply enjoy the hunt. This is a more profound observation than you think. If we live in isolation, we are poor. If we come together with specialization and trade, we prosper. This means that trade is what economists call a positive–sum game. Everyone wins! We all benefit from specializing in a few goods and services and trading for all the rest. (Note: when we say “everyone” wins we really mean almost everyone wins. Given the diversity and peculiarity of human personalities, it is hard to think of any change where you are certain that every single person benefits).

zero–sum game: where one person benefits only when others are harmed

negative–sum game: where [almost] everyone is harmed simultaneously

A zero–sum game would be one in which one person’s gain is someone else’s loss. We mistakenly think an economy is like a zero–sum game sometimes. If Bill Gates becomes a billionaire by producing excellent software, those billions did not come out our expense. We benefited from his software at the same time he profited. After all, if we did not benefit, we would not have purchased it in the first place. Gates is praised today for his philanthropy, as well he should be, but his charity did not need to be motivated by the obligation to “give something back” to a world which made him so rich—he already did, and it’s called Microsoft Windows. It is even possible that Microsoft Windows and Office did more good for the world than his philanthropy ever will.

Price speculation is an example of a zero—sum game. If I believe corn prices are going to rise then I will purchase corn futures contracts, hoping to sell them at a higher price later. Yet I can only do that if someone else is willing to sell corn futures in the belief that prices will fall. If I buy and you sell, I make money and you lose money if prices rise, and for every dollar I earn you lose a dollar. Likewise, I lose money and you make money if corn prices fall, and for every dollar I lose you make money. One of us can only become better off if the other person becomes worse off.

... the framers of the Constitution had something different in mind in granting Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause. The objective was to create an economic union, particularly by ending the trade war among the states that prevailed under the Articles of Confederation.

—Burstein and Rolnich. 1996. “The Economic War Among the States.” Minnesota Public Radio.

A negative–sum game exists when everyone loses, such as in a trade war. Imagine if President Trump seeks to increase the price of American beef by taxing all imports of foreign beef. This would hurt foreign beef producers, and their leaders are not going to retialate by taxing imports of American made products into their country. Trump wanted to help American beef producers while not affecting other Americans, but the decline in trade ultimately hurts all American. If specialization and trade is a source of prosperity, then reducing trade is a source of poverty. The founding fathers understood this well, and inserted the Commerce Clause (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3) into the U.S. Constitution which gives Congress the power to regulate trade among foreign nations, the states, and Indian tribes. One of its prime goals was to prevent the U.S. states from engaging in trade wars with one another

Quotation 5—Bastiat on how we benefit from cooperating with others

There is one way the U.S. states participate in a zero—sum game, similar to a trade war. States compete against each other to lure industries to their area, with the intention of increasing employment in the state. They might give tax breaks to a company that relocates or provide them with infrastructure (e.g., a football stadium) benefitting their business. A state can certainly gain by doing this if they are the only state to provide such incentives, but when one state provides tax breaks to lure an employer the other state must often provide similar tax breaks to keep the employer in place. When all the states engage in this sort of predatory offers the employers get tax breaks without ever having to relocate, and the state governments are starved of tax revenues needed for public goods like education and infrastructure. Sure, a few employers win, but the overwhelming majority of people lose, and since almost everyone is made worse off simultaneously we call this a negative—sum game.

The benefits of specialization and trade have been known for millenia.

Plato’s remarks may be among the oldest references to specialization, but no one expressed its benefits more fully, more eloquently, better linking it with trade, than Bastiat.

(2.b.3) Property Rights and Flexible Markets

Sometimes humans are really to venture into quixotic experiments that result in unfortunate calamity for those involved but a valuable lesson for others. More than once communities have attempted to feed itself without relying on property rights or allowing flexible markets. Usually, they result in man–made famine. In these experiments people were not allowed to own much of anything, and food could not be bought and sold in markets.

Think for a moment about where most of your food comes from. There are a few people who acquire their food as a gift from others. These include beggars, some monks, and children. Most of us acquire our food by buying. Yet, what motivates all the farmers to spend their lives raising crops and animals for us, and what motivates food companies to process the foods and sell it in grocery store. These are strangers who do not feed us out of love, but in pursuit of an honest profits.

The Oklahoma wheat farmer is able to profit from wheat production because she owns the land, equipment, and the wheat she harvests. This means the wheat can only become the possession of another if it is sold at a price agreeable to the farmer (and the buyer). If the farmer did not own the wheat in the first place, they would not be guaranteed any money for producing it, and would have little incentive to farm anything. Not here that property just doesn’t refer to land, but almost anything that could be bought and sold. Property refers to goods of every kind, but also services, like lawyer services or labor at a fast food restaurant.

The farmer can make money because of the existence of property rights, but property has little value if it cannot be easily sold to others at a price favorable to both. It is flexible markets that give property much of its value. A farmer could own her wheat, in that someone else cannot just take it from her, but that does her little good if she is not allowed to sell it. And the fewer limitations on how it can be sold the more likely she is to grow it. The fact that she will be able to negotiate a price also gives her more incentive to produce it. As you will see many Russian farmers did not produce any grain because they could only legally sell it at a very low price, a price so low that they could not have made money. Had they been allowed to be an active participant in the determination of these grain prices, they would have negotiated a price that made it worthwhile to farm—and then millions of Russians would not have had to starve.

These unfortunate experiments occurred with the Pilgrims who settled at Plymouth Rock and the Russians and Chinese during the twentieth century. What follows are two fictional short stories that take place in Russia and China. Though the plot itself is fiction the events really did happen, so it is fiction based on an amalgamation of multiple lives. Then there is a video regarding the Pilgrim experience.

How to starve a nation: Russian edition

How to starve a nation: Chinese edition

A true story of the Pilgrims

This is how economics began

It may sound obvious to you that people will not produce many goods and services unless they can profit from doing so. It would be a hungry world if we all depended upon the charity of others for our food. However obvious this may seen, when it was expressed so eloguently by Adam Smith in his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, the idea took off—and economics as a subject of inquiry was born.

(2.b.4) Decentralized decision–making

Producing large quantities of food for a large population requires us to use our resources efficiently, and this can only take place if you have the people with the right information to make key decisions make those decisions. In the Chinese story above Communist Party officials forced the farmers to apply excessive amounts of fertilizer to the fields. Those farmers knew that was too much, but they had to obey the Party officials. It took considerable hubris for a Party official with little to no agricultural experience to believe she knew more than a farmer, but the Communists viewed peasant farmers as ignorant. Those farmers had better information about the relationship between fertilizer and yields, but the decision was made by a centralized political party. The result was no food production on those fields.

Excessive decision–making by governments is not resigned to just communist rule, nor to despotic rulers. The British Empire once held Tanzania as a colony, and in the 1960’s attempted to resettle the farmers into villages and direct their activities with the aim of “modernizing” them and raising their standard of living. Yet the administrators in charge of this project did not have the expertise make such decisions, and so they tended to resettle Tanzanians and direct their activities in a way that eased their administrative burden. Instead of relocating them to areas ideal for agricultural production and choosing the crop mixes that are suited for that area, they forced them onto areas that made it easier for the administrators to monitor. Laws were passed dictating what types of crops should be planted, and in some cases these selected crops lost the farmers money. They were forced to adopt agricultural techniques that require mechanization, but then failed to deliver the tractors and other machines when they were needed.[S1]

It was a fiasco, a tragedy. Unlike the Russian and Chinese Communist Party, the British were not trying to just take wealth from the farmers—they were sincerely trying to help them. Their mistake was thinking that because they were white, British, and from a developed country, their paternalistic rule would help the people of Tanzania. What the British did not realize that the Tanzanian farmers possessed certain sorts of information the British did not—information that was localized and relevant to that part of Africa.

Decentralization is desirable for two reasons.

- Decisions should be made by those who are affected by the outcomes. In our Tanzania example the government officials would not bear the brunt of unwise decisions. That was the Tanzanian’s burden to bear, and so the British administrators did not have the incentives to make decisions in favor of the residents.

- Decisions should be decentralized because information is disseminated throughout an economy. Even if a central government agency wants to accumulate all the information in an economy needed to make good decisions, it cannot. Information is too dispersed, and the government officials don’t even know all the questions to ask. The Tanzanian farmers knew localized information about the different soils in the area and the performance of different crops. They had a localized, specialized knowledge not possessed by their British colonizers. Moreover, the nature of this information is such that, even if the British tried to collect it from the people, it simply cannot be done adequetely. Because it is impossible to aggregate information effectively by a centralized organization, economic decisions should be shared with the population. In our Tanzania example, this means the British should allow the Tanzanian’s to decide where their villages should be located, what they should raise, and how they should farm.

One part of a decentralized economy is to allow markets to help make decisions. Crops can be supplied with nitrogen fertilizer through the use of (1) chemical nitrogen (2) manure (3) or the planting legume plants. Which of the three methods is best? All three have advantages and disadvantages. A legume is a plant that extracts its own nitrogen from the atmosphere, so it gets its own nitrogen for free. This is a great way to fertilizer plants, assuming that people want to eat the foods produced by legumes. Indeed, people do like beans and peanuts (two legumes), but they don’t want to only eat legumes. How do we know if we already produce too many legumes? The price of foods like beans and peanuts is a good clue. If the price is very low, that is a signal that we already have too much, and signals to farmers not to plant any more.

Manure is a great fertilizer, as it allows us to take a waste product and turn it into food. It is also usually inexpensive to acquire from a farm. However, manure are bulky and expensive to transport. Chemical nitrogen on the other hand is inexpensive to transport, but is not cheap to produce. So, does it make more sense for any one farm to fertilizer using manure or chemical nitrogen? It just depends on the location of the farm relevant to manure and compost sources, and the best indicator of this proximity is the price of acquiring delivered manure. Again, the simple price of manure versus chemical nitrogen provides a wealth of information about which sort of fertilizer is best for a farm, so smart decisions about fertiizer are made by letting the farmer make those decisions, based on the prices she observes, and whatever makes her the most money.

(2.b.5) Respect for honest profit–making

—Aristotle, approving of the degrading of business-people, as quoted in: McClosky, Deirdre N. 2011. Bourgeois Dignity. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL. Chapter 41.

“Comrade! you have the air of a merchant of tennis-balls; and you come and sit yourself beside me! I am a nobleman, my friend! Trade is incompatible with nobility.”

—Hugo, Victor. 1831. The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The setting of the story is 15th century France, whose main character is Quasimodo.

“Unlike in France, where trade and commerce are scorned as common, in England, the commercial life and the diversity of religion itself have created a voluntary, peaceful, tolerant interaction, that enriches and betters mankind.”

—Alan Charles Kors. 2001. Voltaire and the Triumph of the Enlightenment. Lecture 4: Philosophical Letters, Part II. The Great Courses.

Today we admire successful business people who made their profits honestly. People do not avoid going into the business world because they think it “beneath them”, and most people expect they can live a meaningful life in the private sector just as they could the public or non–profit sector. Because people who made their fortunes—obscene and modest fortunes alike—honestly are admired our best and brightest enthusiastically enter the business world, including the world of food, helping to make the food system effective.

People did not always view business in this manner. It used to be that making money by trading in markets was considered ignoble. In eighteenth century France a nobleman could lose his noble status if he engaged in commerce (buying and selling goods). This caused the French to scorn business, but things were not like this with the English and the Dutch, and this is one of the reason the Industrial Revolution began in Holland and the United Kingdom. The truth is that people want more out of life than money. They want respect, to be admired by others, and since our society allows them to acquire this through honest business that gives people even more incentive to use property and markets to produce and distribute food for others.

Just respecting an honest profit is not enough. For a society to successfully develop and employ more productive technologies it must allow for creative destruction to take place. Centuries ago most people in the developed world were farmers, but that number is now less than 2%. Most of this change came about from new technologies like tractors and other machines which allow one person to produce much more food than their ancestors. This releases a large portion of the population to produce other goods and services, like trucks and health care. The process by which this came about necessarily causes many farmers to go bankrupt and have to seek work elsewhere. The same is true for blacksmiths, and carriage makers, and lantern producers. If these individuals had not been put out of business by new businesses, and if they could have used political power to stop new technologies, we would not have the productive agricultural technologies today. When we say that we have respect for someone who makes profits honestly, this holds true even if that person put others out of business by providing its customers with more value—a better product at the same price, a lower–priced product of similar quality, or the like. Progress is good for everyone in the long–but always a burden for some in the meantime.

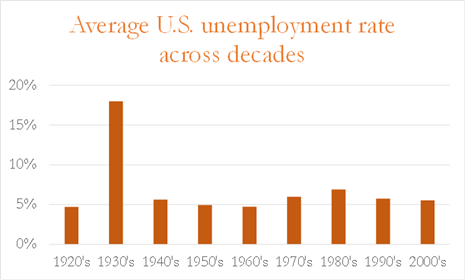

Think of all the jobs that existed in the 1920’s that do not exist today. And think of all the professions that exist today that would have been inconceivable in the 1920’s. Despite the complete transformation in the American economy in the last century, the unemployment rate (the percent of people who want to work but cannot find a job) stays about the same. Only during the Great Depression of the 1930’s does it differ. What this means is that in a dynamic economy entire industries can be destroyed but will be replaced with new industries, such that the same amount of people who want work will find work.

Remember, we say it is good if someone reaps profit if they produce more value than their competitors. Yet we know that some people earn money not by providing more value but by being dishonest in their dealings or through the use of political power. A form of capitalism that operates based political power is referred to as crony–capitalism, and it is this type of capitalism that pervades countries like China and Russia. The U.S. has problems with cronyism also, though to a much less extent. Politicians need money to win elections, but the ordinary American is not going to donate much. Big corporations will, though, and so politicians have learned that the best way to raise money is to take donations from business–people and then repay them by passing laws in their favor.

Consider 1995, when a bill was being considered to abolish $49 million subsidy to tobacco companies. As the bill was being voted on representative John Boehner was caught on the House floor distributing checks from tobacco companies. And guess what? The bill failed and the companies kept their subsidy! [B1]

When the private sector comes to believe that it can make more money by buying favors from politicians than creating more value for its consumers, the economy stops working for the people and becomes a negative–sum game of who can influence politicians the most. This is why any market economy must have integrity for it to truly be a positive–sum game and benefit everyone.

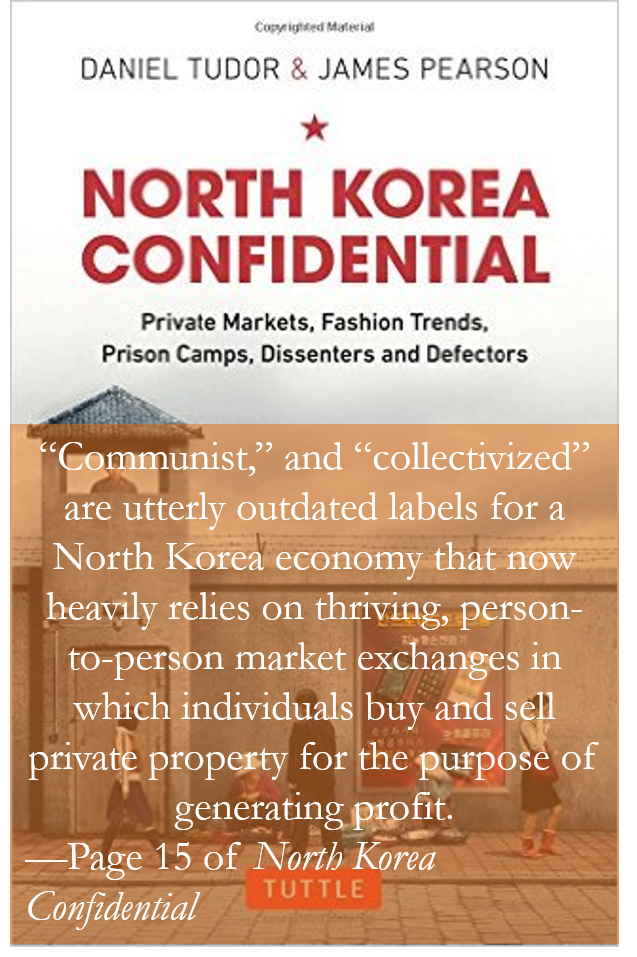

Even North Korea realizes this now.

The North Korean government may be malevolent but they are not stupid. The wealth in modern capitalistic democracies and the rising living standards in China has made it clear to them that private property and free markets are needed for an adequate food supply, and so in the last twenty it has made a number of adjustments. The average citizen has an official government job, but it makes them little money and they avoid working in it. Bribes are paid so that they don’t have to show up, and they often claim medical problems. They avoid their official government job because they spend as much time as possible in their private jobs where they buy and sell things and engage in economic production to make money. Most of the food they eat, and most of the money they spend, come from these illegal private jobs, not their official government ones.

Officially there is no private property, and officially market trading are illegal, but the government has decided to look the other way, and usually charge money for looking the other way. In fact, a successful business generally has to pay government officials 30-40% of its profits for the right not to be arrested. Why does the Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un allow this? Because some of that money finds its way to him. North Koreans grow food and sell it in farmers markets. They import goods illegally, and sell them on the black market. They produce goods in buildings resembling factories, and even export.

Like the U.S., most of what North Korea consumes is due to technology, private property, and free markets. The only reason is that since property and market trading is illegal it is very costly, and so less of it than in the U.S. Consequently, there is less of everything compared to the U.S., except misery.

(2.b.6) A sincere sense of humanity

Feeding a large population requires more than just producing lots of food. The world produces about 2,700 calories each year [F2], which is plenty to feed everyone. Yet one in nine people still do not get enough food to live a healthy life [W1]. There has always been a problem of food distribution. No matter how prosperous a nation becomes there will be some individuals who have difficulty acquiring food. Even in the U.S. about 5% of households have serious food security problems [F3]. Without food charity from the private sector, non-profit organizations, and/or government programs, only a portion of the population will be fed well. In the U.S. we have government programs in the form of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits and private charities like the Salvation Army who provide free food. If we do not empathize with the poor and lend a generous helping hand, no amount of agricultural technology will ensure everyone eats well.

One of the most famous famines occurred in Ireland in the mid-nineteenth century, and the cause is usually attributed to a potato disease that dessimated Ireland’s potato crop. That is indeed why all the potatoes died, but not the real source of the famine. During this period most of the agricultural land was owned by the British and leased to Irish tenants. The tenant farmers were required to produce goods like wheat and beef for export to earn the small plots of land on which they could grow their own food. The British landowners provided such small amounts of land for the Irish to sustain themselves that they had to grow mostly potatoes due to its high calorie production per acre. The Irish didn’t want to eat a diet composed mostly of potatoes. They had no choice.

When the potato disease did strike it killed the potatoes but not all the other crops the Irish were producing for their British landlords. In fact, there was enough food produced in Ireland to feed everyone, but instead of allowing the Irish to eat these other food sources the British exported it for their own profit. The Irish starved not because of a potato disease but due to selfishness of their British landlords.

Although the world still experiences shortfalls in food production due to natural events like drought and pests, so long as governments are willing to pursue helpful policies and people are eager to extend brotherly love, hunger is rarely a problem. Hunger and nutrient deficiencies are almost always man–made problems. [O1]

(2.b.7) Protection of natural resources

In Mongolia nomadic herders are experiencing higher incomes due to the production of cashmere goats, used to produce the famous cashmere fabric. The animals grow fast, are hearty, and their fur sells for a high price. Thirty years ago these goats were only 19% of all Mongolian livestock, whereas today that number is 60%.

The problem is that this cannot continue, for the goats are destroying the grasslands. When they graze they pull the entire plant out of the ground—roots and all, killing the plant. Other livestock like cattle, camels, and horses merely cut the blades of grass, allowing it to regrow. They have caused so much plant damage that in many areas the grass no longer grows, and what used to be fertile steppes is now looks like a desert. Up to 65% of the Mongolian grasslands are now destroyed due to the proliferation of the goats, and if they do not change this course within ten years much of this will not return.[S3]

Food production requires the use of natural resources, but it must be used wisely. Great amounts of food can easily be produced by exhaustion of natural resources today, but of course that is not sustainable.

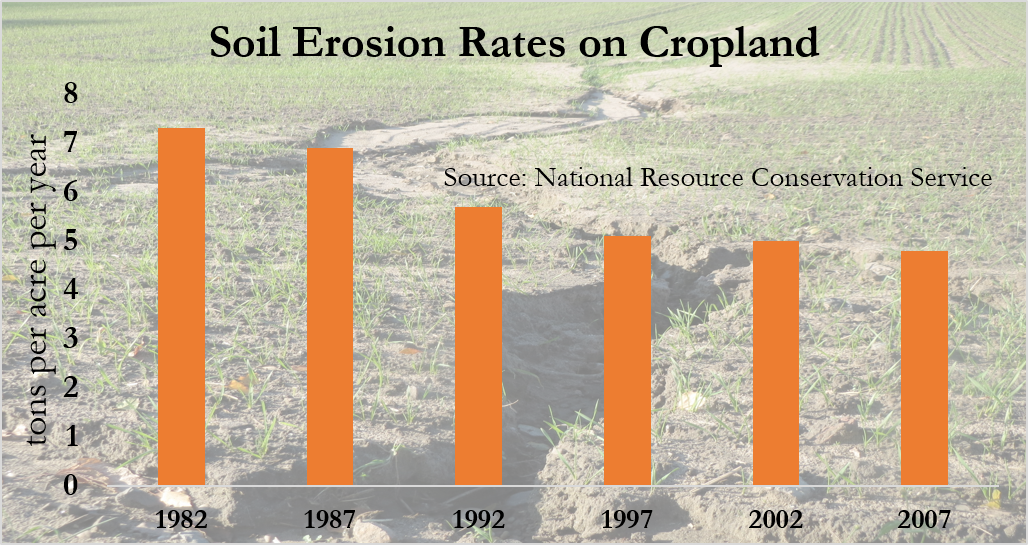

One of the most important resources is our topsoil, yet from the beginning of agriculture we have been losing it. It is very difficult to farm without experiencing soil erosion, especially in the past. Many great civilizations faced their demise partly due to a dwindling soil productivity. We tend to think of Greece as a rocky, barren landscape, but before the land was plowed intensely it was lush and green. Year after year of erosion destroyed is productivity capacity, though.

The challenge to limit soil erosion is still with us, but we are doing better. The figure below shows that while we are still losing topsoil the amounts we use is dwindling over time. The cause is many reasons, but I will categorized them as two. First, there is the will. Today our government, our universities, our farmers, and concerned environmentalists are putting real resources into encouraging agricultural methods that preserve the soil and developing new technologies to limit erosion.

New technologies constitutes the second reason soil erosion is falling. The advent of no–till agriculture deserves most of the credit. In the past plowing the land was essential for managing weeds. Today, the combination of genetically modified crops and better pesticides allow us to manage weeds with safe pesticides. No–till systems have advanced so much that many farmers today never even plow the land at all.

(2.c) Consensus on the Great Enrichment

Not everything in this chapter is completely true. There have been societies able to feed themselves well without formal institutions of private property, and without the type of free markets described above. Many Native American tribes for instance shared communal property, where food was largely owned by the entire tribe. There was specialization, especially between people of different genders and ages, but decentralization may have been minimal. In some ways the tribes had an effective food system, especially in regards to food justice, as everyone in the tribe was entitled to their share of the food—note that everyone was responsible for their share of the work, also.

Ancient Egypt under the Ptolemies ran an agricultural system similar to that of Russia and China in the twentieth century, and they made it work reasonably well.

Yet for the most part, in a nation with a large population and an orientation towards an individualistic culture, the factors listed above are those that are usually needed not just or an ample and healthy food supply, but for prosperity in general.

Economic history has looked like an ice–hockey stick lying on the ground. It had a long, long horizontal handle at $3 a day extending through the two–hundred–thousand–year history of Homo Sapiens to 1800, with little bumps upward on the handle in ancient Rome and the early medieval Arab world and high medieval Europe, with regressions to $3 afterward—then a wholly unexpected blade, leaping up in the last two out of the two thousand centirues, to $30 a day and in many places well beyond.[M1]

But what causes the Great Enrichment: the extraordinary explosion of economic growth beginning around 1800 in Western Europe and its offshoots (including the U.S.) and eventually spreading to other countries like China and India? You might find it surprising that economists can’t really explain the Great Enrichment. Though we can point to many factors that act to increase prosperity—with many of those factors listed above—what we cannot do is to use them to show why it made the period 1800 so different than in years past.

The best studies thus far point to two cultural changes that are related to modern agriculture, and so is worth studying here.

(A) A change in attitude toward Nature. That is, “Nature” with a capital N, meaning Providence, or the order of the universe—one God, or many gods, however you think about the universe and human’s proper role within it. Starting primarily with the Enlightenment in the seventeenth century western Europe humans began deciding that it was appropriate to study nature and harnass it to meet our material needs. Of course some people in every age and culture believe this, but observe how only in the last few centuries has it been okay to dissect humans to improve medicine, view something other than the Earth as the center of the universe to enhance physics, and allow people to suggest ideas that at first seem heretical without burning them at the steak?

(B) A growing belief in the equality of people. It is no coincidence that the Great Enrichment occurred at the same time the European aristocracy was losing power to the commercial businesspeople. Increasingly people were learning that a middle–class businessperson could have equal virtues and intelligence as the great Nobility. Great ideas could be found at the estate of a Duke, or the cottage of a leather artisan. Today, we expect our most ingenious people will be found not in the mansions of billionaires but in the garages of the everyday citizen. It does not surprise is if some 22 year old nerd from a public school comes up with a clever idea that makes him or her billions. Speaking of “him or her” today we are open to new ideas from both males and females. Simply by being less sexist we release half of the population to offer their unique ideas on improving our lives.

—Steven L. Goldman in Lecture 28 of Great Scientific Ideas That Changed the World.

What these two changes did was to release a cultural valve that were suppressing new ideas, and consider what this has done for agriculture. It seemed a crazy idea that advanced chemistry could extract nitrogen from the sky and use it to fertilizer crops, but that is exactly what Fritz Haber accomplished. The first steam engines were too inefficient and awkward for much use, but today about the only thing to actually touch the dirt of a wheat field is a machine. It takes some audacity and imagination to believe that we can simply edit the genome of a plant or animal, but that is exactly what we have accomplished.

You see, although we need things like property and markets to make sure food is produced, but without ideas we will not be able to produce more food than before.

References

[B1] bulletin.represent.us. November 23, 2016. “Flashback: Boehner hands out tobacco lobby checks on House floor.” Accessed December 14, 2016 at http://bulletin.represent.us/boehner-tobacco-lobby-checks/.

[D1] Dikötter, Frank. 2010. A People’s Tragedy. Bloomsbury USA.

[F1] Figes, Orlando. 2014. A People’s Tragedy. Bodley Head.

[F2] Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Accessed December 31, 2016 at http://www.fao.org/docrep/x0262e/x0262e05.htm.

[F3] Feeding America. Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics. Accessed December 31, 2016 at http://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/impact-of-hunger/hunger-and-poverty/hunger-and-poverty-fact-sheet.html.

[G1] Information taken from lectures by Robert Garland at The Great Courses titled The other Side of History: Daily Life in the Ancient World.

[M1] McCloskey, Deirdre. Page 2. 2010. Bourgeoise Dignity.

[O1] O’Grada, Cormac. 2009. Famine: A Short History.Princeton University Press.

[S1] Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State. Yale University Press.

[S2] Sullivan, Tim. October 2013. “Now You See It.” National Geographic.

[S3] Schmitz, Rob. December 9, 2016. “How Your Cashmere Sweater Is Decimating Mongolia’s Grasslands.” National Public Radio.

[W1] World Food Programme. Hunger Statistics. Accessed December 31, 2016 at https://www.wfp.org/hunger/stats.