Explore with focus groups

When Lewis and Clark set out on their now-famous trip, they had two very specific objectives: to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean and provide information about what resided west of the young America. Their objectives were specific but their methods were not. They could not plan in advance exactly where they would travel and how they would return, for those decisions had to be made based on what they encountered along the way. You can never outline in stone how one will explore anything, for the very definition of exploration means you do not know what will happen along the way.

The same could be said for focus groups.

Video 1—Humorous depiction of Focus Group (advertising the book Truth in Advertising)

Source: Accessed July 26, 2016 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gh1UM5c4M84

Focus Groups, Defined

A focus group is a session (1) involving a small group of people, usually 5 to 10 (2) who mostly answer open-ended questions posed by a moderator (3) and are allowed to interact with each other and inject additional comments whenever they like, even if not directed addressed by the moderator. Think of a focus group like a guided conversation. The reasons groups are used instead of individual interviews is because people feel more comfortable talking and are more talkative in groups, the social interactions can help people recall things they might otherwise forget, and the group dynamics often provide valuable information about the role peer pressure in the product acceptance. We usually think of focus groups being about a consumer product, but the subject could be anything, like a service provided by a company, a service provided by government, the local school system, a political party, and the like.

When people interact in a group they often share and compare their perceptions and experiences, and that creates a system of feedback and detail you just don’t get in a personal interview. Because participants are largely answering open-ended questions you get to hear how they talk about an issue in their own words, which can be critical information in designing advertising strategies. If the purpose of the focus group is to explore particularly sensitive topics, then a well-chosen group can elicit insightful comments. For instance, if you want to understand how poor households manage their food budget or choose between low and high quality produce, having a group of low-income individuals together can create a sense of camaraderie and safety that might not exist if you put low- and high-income people together, or if you conducted one-on-one interviews [1,2].

The role of focus groups

Video 2—The effectiviness of focus groups (Episode “A System on Trial” from The Grinder)

People conduct focus groups to acquant themselves better with the thoughts and behaviors of a particular segment of people. The video below shows an actual focus group designed to compare two different types of tops for BBQ sauce bottles, one being a new top called LiquiFlapper. They were even asked to pour sauce from the bottles and provide comments on their experiences. Some liked the flip top because it helped people direct where the sauce goes and it keeps it from dropping. The flip top was seen as being more economical as it was thought to waste less sauce. Towards the end the moderator conducted a poll to determine how much more people would pay for sauce with the LiquiFlapper, discovering people would pay $0.10 to $0.25 more.

Video 3—Evaluating tops on sauce bottles

Broadway producer Ken Davenport has expressed his fondness for focus groups. He admits that because he is immersed in the business he has a hard time understanding how the general public views musicals. Producers often develop logos to promote their musicals, and sometimes they put the faces of actual actors in the logo, but the focus group warned that if they see a logo with the face of a person they do not recognize, that tells them the musical doesn’t have any starts. Before they attend a show they really want to know what the story is about—they don’t just go for the music [4]. These remarks have helped Ken promote his shows, and though they may sound obvious to in hindsight, it often takes focus groups to identify what later seems obvious.

Bellingham Public Schools in the state of Washington conducted focus groups on its food service, finding that the community wanted the school to offer more local foods, and that many participants associated local food as being healthy food. There was a concern that elementary students were not given enough time to finish their lunch, and that there seemed a contradiction between what students were taught in class about healthy eating and what they were served in the cafeteria [5].

Other times one might want to know what aspects of a politician’s speech people respond favorably to, as in the focus group concerning Donald Trump below.

Video 4—Focus Group on Donald Trump

Companies and government agencies might be interested in what type of materials best promotes food safety literacy. Focus groups have been used to compare different reading materials and indicate which ones they are more likely to read, and have also been used to assess how ordinary consumers interpret food safety information [6].

Focus groups exist to help people not make big mistakes. What seems culturally acceptable to one group of people may be insulting to another. In 2016 Bud Light was scolded by the public for running an advertisement campaign where Bud Light was said to help remove the word "no" from your vocabulary. Most of the American public saw the advertisement as encouraging unconsenting sex, but it seems the Anheuser-Busch company saw nothing wrong with it. Many wondered, didn’t they test this slogan with a focus group? Surely that would have revealed problems? Maybe they didn‘t, but a marketing professor at Boston University remarked that if a focus group was held it probably consisted of young men, as they are Bud Light’s primary demographic, and this demographic may be less likely to be offended by it (as Jon Oliver suggests in his humorous segment below) [3]. To assess its future advertising campaigns, the company might also show the commercials to focus groups consisting of other demographics to ensure it is not insulting to society at-large.

Video 5—Bud Light obviously needs better focus groups (From This Week: May 4, 2015)

No big decisions should ever be made based upon focus groups alone. Companies who place excess emphasis on focus groups can forgo profitable opportunities or embark on unprofitable ones. Think of it like this. Suppose you have developed a new recipe for mayonnaise, and are pondering whether it would be profitable to produce and sell. You develop a habit of having friends taste it whenever they happen to visit you. Sometimes you have them taste it plain, sometimes you put it on food, and you ask them for their honest opinion. In total about 20 friends have participated in your little experiment. Do the remarks of your friends matter? Of course. Would you base your entire decision of whether to pursue it as a business based on their comments alone? No, you should not. The same could be said for focus groups.

Perhaps surprisingly, marketing research experts often say that companies have a tendency to place too much emphasis on the results of focus groups, and they are the people paid to conduct focus group sessions. One must always remember that focus groups can only tell you what people know, what people remember. They can be bad for innovation. If you are trying to design a new advertising campaign based on an idea that people have never seen before, it is doubtful that an idea for such a campaign will be discovered in a focus group, as the video below demonstrates.

One should not expect great new ideas to come from focus groups. People generally can only tell you already know, whereas the entrepreneur is usually trying to design something people have never seen before. In the days of the horse and carriage, it is doubtful a focus group participant would have suggested that someone like Henry Ford should develop an assembly line that can produce a carriage able to be moved by an internal combustion machine.

I encourage you to watch this entire video, as it gives some very good tips on leading and using focus groups. People even have a hard time recognizing the benefits of a new product, as the strangeness of it is just more salient that its obvious benefits.

Video 6—Focus Groups on the show Mad Men

Selecting the groups

A single focus group session will have between 5 to 10 participants, as this maximizes the amount of intereactions between the subjects, but most studies will conduct more than one focus group session. The more sessions, the more observations, and the more information—and the greater the costs. One marketing research group estimates that it costs a little over $20,000 to conduct two focus groups on the same evening, with 10 people in each group [7].

There are no hard-and-fast rules for how many focus groups one should conduct, but here are some suggestions. For each strata to be studied, most research will conduct 3-5 focus group sessions, where a "strata" is a particular type of individual you wish to study that is best studied in groups of that strata only. Let us return to Bud Light’s slogan "Remove the word 'no' from your vocabulary". Suppose that you want to know how both young males and females of all ages interpret the slogan. Those are two different strata because they are different types of people who are best studied in separate focus groups. If you place males and females together in the same room, a female may quickly remark that it suggests sexual assault, and if that happens, the males may shut down and be fearful of saying anything. This means you would want to conduct 3-5 focus group sessions for young males and 3-5 sessions for females of all ages. However, if you were studying how American consumers in general like the taste of fresh pecans versus pecans you buy at the store, there is no need to separate men and women. Then your strata can just be the American population and you can conduct 3-5 sessions, making sure the demographics of your participants resembles—though it doesn’t have to match perfectly—the demographics of the American public.

How do you determine when people of different demographics need to be studied in separate sessions? This requires simply common sense, but one thing to keep in mind is power differentials. If the composition of your group is such that some people may have more power than others, you should try and separate the people so that when they all sit down for a session they feel they are with like-minded people with whome they may converse freely.

Recruiting the participants

It is important that your recruiting process brings the right people to the session. Here are some tips to doing so.

- When you contact people by phone, email, flyers, or the like, be careful what you say about the purpose of the research. If you want to know about the thoughts about the general public, don’t say things that might alienate a certain segment of the population. For instance, if the idea is to explore what Americans in general think about the gestation crates used to house pregnant hogs, you don’t want to say that the purpose of the project is to discuss the treatment of hogs because that might cause animal rights advocates to be more enthusiastic about attending than the ordinary meat-loving American. Vegans and animal rights activists would be overrepresentative in the group, and might give the false impression that Americans care more about livestock than they really do. I generally prefer to just say something generic, like the purpose of the project is to discuss people’s preferences for food. I once hired a marketing firm to recruit people for a focus group, and was forced to go with the lowest bid, which was Ebony Marketing Research. Not surprisingly, when they called people to recruit them for the sessions, and introduced themselves as "Ebony Marketing Research", they elicited far more African Americans than one normally finds either in focus groups or in the American population. My sample was biased because I was forced to use a marketing firm that would unintentionally recruit an unrepresentative group of participants.

- Most people would not attend a focus group for free, so if you did not pay people to attend you would end up with a strange group of people who have nothing better to do. Thus, subjects must be offered something for participating, and usually this compensation takes the form of cash. The exact amount depends on the region—in cities the compensation might be $100-$150 while in small towns it might be $50-$100.

- Make sure your sessions are held at convenient times. Most people could not attend a session held at 2:00 PM on a Thursday because they are working. However, if you are studying stay-at-home moms or the unemployed that might be an ideal time.

- Be mindful of the medium of communication you use to recruit. I was hired a firm to recruit people by phone, and I ended up primarily with senior citizens, and virtually no young people. Younger people do not use landlines as frequently as the elderly. I don’t even answer our land-line at home. That would not have been a problem had I been studying the elderly, but I was trying to acquire a representative sample of the U.S. Conversely, if you used email to recruit individuals you might find yourself with too few senior citizens. If you wanted a sample that is representative of America that is bad, but if your purpose is to study the thoughts of young people that is good. Most marketing firms recruit people through a variety of mechanisms, including phone and email but also word of mouth. My aunt runs a marketing firm and she will find people who work at an organization, given them information about participating in focus groups, and ask them to take flyers or sign up sheets to their workplace.

The art of focus groups

A focus group moderator should not try to firmly control a session, but to gently guide it. The idea is to ask some very simple, mostly open-ended questions that subjects can easily answer, but questions that also begin a conversation. A session devoted to how people choose which grocery store to patron should not simply ask a series of yes/no question, like, "Raise your hand if you just go to the closest store ... Raise your hand if you just go to the store with the lowest prices ... Raise your hand if you patron the stores with the freshest produce." Instead, the moderator should ask a question like, "Think about your average trip to the grocery store. What store did you choose, and how did that store differ from others you could have shopped at?" Notice that we don’t ask why they choose the store. "Why" questions are rather confrontational and can cause defensiveness. Instead, the reasons why will naturally emerge as they describe the store.

At the beginning a subject may need to be called upon to give the first answer, and then to encourage others to chime in you could follow with questions like, "Does this sound like the grocery store you tend to shop at? How does your preferred store differ?" It won’t take long before people are anxious to contribute their remarks to the group, and the group may interact so smoothly that the moderator can back off and just allow the group to converse organically.

Audio 1—Listen to this talented focus group moderator

That said, the group should retain its focus, and one trip to doing this is to periodically take a poll to see where the group as a whole stands, and then use the result of the poll as a way to transition into another topic. If most subjects seem to choose stores based on a combination of proximity and location, the moderator could ask, "It sounds like a store’s location and prices are the most important factors determine where someone shops. Raise your hand if this describes you." If someone did not raise their hand, you could then ask them, "Jim, you say location and price are not the main attractions, so what criteria do you use for choosing a grocery store?" Of, if another objective of the focus group is to determine why people patron multiple stores, you could say, "Okay, sometimes people shop at more than one store, even in the same week. Describe the conditions that would cause you to shop at more than one grocery store in the same week."

Video 7—An unfocused focus group (From Love, Season 1, Episode 3)

It takes time for a ripple to travel from the drop of water to the shore, and so you want to make sure that you allow enough time for each question to be discussed thoroughly before moving onto another topic. Designating about 5-10 minutes for each question is usually sufficient, and since focus groups last about 1.5 to 2 hours, this means you should limit yourself to about 8-12 questions.

First impressions are important, so you want to make sure the subjects understand what kind of information you will want from them and they must be put at ease. I really like the way way the moderator in Video 4 begins the session, but that kind of approach isn’t always appropriate. I think the most important thing to accomplish in the introduction is to tell the subjects that you are just a moderator and have no personal or professional ties to the item of discussion, and that the purpose of the session is to listen to their true feelings about the topic. Tell them that the session is being recorded, and specify whether it is audio or visual, but that their comments are not linked to their contact information and thus their remarks are anonymous.

Video 8—Watch a real focus group regarding three pecan varieties

The questionnaires used can be downloaded here

The transcript from this focus group is available here

Setting the mood

The key to conducting effective focus groups is to make people feel comfortable telling the truth. This is harder than it may seem. During most of our days we are not expected to be completely honest, or is it in our interest to be. When we talk politics we make our beliefs more black and white than they really are. When gossiping people want you to say good things about them and bad things about others. Our parents want to hear what wonderful people we are, and our bosses don’t want to know anything they can get in trouble for knowing. People can be vindicative when they hear the truth about themselves, and lies—both big and small—often benefit us personally. In political campaigns, few statements are entirely true, and the people want it that way. Ordinary life is much the same.

So how do you go about creating an environment where people will want to be truthful? Here are some suggestions [1,2,8].

- Ensure anonymity: People will be excessively careful about their remarks if they believe those remarks can be associated with their name and contact information. You may have contacted them by phone or email, so they know they have some of your contact information. You will also ask them their name, as you will refer to them by this name during the session, so make sure you tell them at the beginning that although the session is being recorded none of their remarks can be linked to their contact information.

- Tell them you want their complete honesty: It may seem obvious but they need to hear it.

- Portray yourself merely as a conduit for their thoughts: Never have the inventor of a product lead a focus group about the product, as they might become obviously sensitive to a criticsm about it or obviously delighted about praise. Just as people do not like insulting others to their face, they will not want to tell the president of a company bad things about their services. This is why companies often rely on third-party research firms to conduct the focus groups.

- Curiosity is the only emotion: Always demonstrate a curiosity for thoughts of the subjects but try and avoid showing approval or disapproval of any particular comment. The best way to show curiosity is to ask a subject to expound upon a thought further or ask if others agree.

- Control the group: Interviewing people in groups has its pros and cons. The advantage is that subjects can feed off one another in a group, allowing them to think of things they might not consider if interviewed alone. If the topic concerns preferences for pecans, a subject might have forgotten how their grandmother used to make pecan pies until they hear another subject mention it, after which they realize why the taste and smell of pecans always brings them such comfort and thoughts of home. The downside of groups is obvious to anyone who has been in a group: one member can dominate or another the others, making the others reticent from participating. It is the moderator’s job to make sure this does not happen. They should ensure that each person participates equally and prevent one person from having an undesirable influence on the others. If you have a subject who is particularly talkative, use them as a straw man to encourage others to talk. Suppose they are talking about all the different ways they use pecans in their recipes at home and show no sign of stopping (like Forrest Gump’s friend describing all the different types of shrimp he cooks), find a polite way to interrupt and say to the others, "Does anyone else use pecans when they cook?" If one member is particularly opinionated, a way of eliciting everyone’s participation is to call for a vote. Jim says you can only really enjoy pecans if you shell them yourself because it makes it more fun and paces your consumption. He says this as if it is a fact. Okay, then, say to the group, "Raise your hand if you agree with Jim." It is okay for members of a group to disagree, even debate, so long as they do so cordially. In fact you can sometimes get particularly good information from disagreements.

- Refer to them by first names: Before the session begins the moderators should make sure they know the first names of each person, because a particularly silent subject is more likely to begin talking if asked to by name. You don’t want to refer to them by their job descriptions though, or say anything about their occupation or status, as that can create an aura of a class system that will impede discussion.

Video 10—Focus Group from Silicon Valley (Season 3, Episode 9)

- Ask them to write: It is sometimes desirable, before a discussion begins, to give subjects 2-3 minutes to write down their thoughts on a subject. It gives them some time for self-reflection and reduces the chance they will change their mind during the session.

- Don’t write yourself: The session will be video or audio recorded, so there is no need for you to take notes. Though it may be tempting to record remarks you feel important, or ideas about other questions to ask, if you do write something then the subjects will assume what was just said was more important than remarks that were not followed by your writing. This alters their comments, and they are likely to try to make similar remarks that will also be recorded.

- Positives and negatives: Don’t just dwell on the positive aspects of a product, or the negative, as that will give the subjects the false impression that they should champion or disparage the product. Ask for both the positive and negative attributes throughout the session, so that the subjects are constantly reminded that their purpose is to provide their thoughts on the product, not to just promote or just criticize it.

- Hide observers: It is likely that company representative will want to observe the focus groups, but having them present in the room will bias what subjects say, so it is an almost universal trait that focus groups are held in rooms with one-way mirrors so that company representative can see the session without being seen themselves.

- Dress:The moderator should dress in a professional manner to make it clear that they are the leader of the session.

- Moderator knowledge:The moderator should be knowledgeable but not a know-it-all. They should know enough to ask the right follow-up questions, but not so much that they flaunt their knowledge or lead the respondent in questioning the subjects.

- Moderator traits:The moderator must have a good memory, be a good listener, treat each person equally kind, always keep the big picture in mind, and must find a way to control problem participants without alienating them.

- Group composition:Think carefully about the group composition. There are situations where males might be more honest in the absence of females, or times when young adults are silent or dishonest in the presence of the elderly (imagine a focus group on condoms with a mix of senior citizens and teenagers!

- Allow discussion to flow naturally: People will only feel free to provide their sincere thoughts in the context of a safe conversation where they feel like they are partly in charge. Sometimes moderators want to stick to closely to their outline. Suppose the moderator has a list of topics for a pecan focus group, and the last item on the list is how they remember eating pecans as a child (e.g., shelled in prepared foods or shelling the pecans and eating them as a snack?), but sometims mentions this within the first two minutes of the session. You do not want to tell that person that this particular topic will be covered later, because then they and others will be reticent to return to it. Moreover, there might be a reason it was brought up soon, before asking, and by passing their comments over you might never find out.

Video 9—Donald Trump conducts a focus group on Donald Trump

The last question

The subjects may have an important comment that was not specifically asked about in the moderator’s questions, so always make sure you ask something like the following: Is there anything else that you would like to add that I did not specifcally ask about today?

Analyzing focus group data

Step 1—Transcription. The first task after the group sessions are complete is to transcribe the interviews into written form. This is where a person (called the transcriber) watches the video (or listens to the audio) and records the remarks made by each person, identifying the person not by their name but by a unique identification number. This number should identify both the person as well as session the person attended. As an example, a person named Fred might be given the number 507, where the "5" means they attended the fifth session and the 07 means refers to the person. So there might be another person with the number 407 or 607, but only one person with the number 507. The transcriber not only records the words that are said, but how they are said and any non-verbal communication involved. For example, if a person cries while speaking the transcriber notes that the person cried when the remarks were said. It is okay to summarize their main ideas rather transcribe their remarks word–for–word.

Step 2—Familiarity. Next one must ruminant on the transcripts and recordings. I advise that the analyst watch the video or listen to the audio, even if the transcription has already been made. Do not write down anything. Do not make any plans. Just listen to it all and let it soak in. Only start compiling actual results when all sessions have been observed.

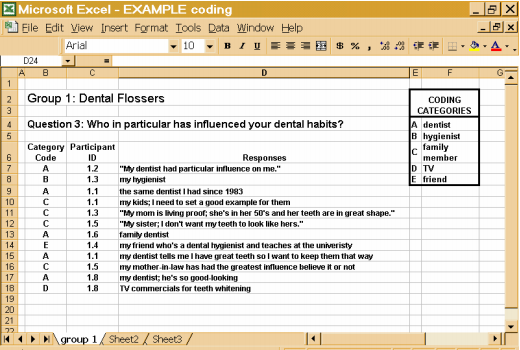

Step 3—Coding themes. Since a focus group is a group interview, consisting of questions and answers, it is obvious that your data analysis should describe the answers that people provided. This is more difficult than in the case of a survey though, because people may use different words to describe similar things. The researcher cannot provide a simple table of the number of times a particular answer was provided, but they can group responses into themes and describe the frequency of those themes. The figure below shows an example of developing a dataset from the transcripts. After completing step 2 the person then reads through the transcripts and marks the presence of certain themes. Figure 1 is a case where a group of eight people were asked about individuals who had influence over their dental habits. The analyst creates a code for different answers, like A = dentist. Then, whenever a person indicates that their dentist has a particular influence the analyst may write "A" above the comment, and then record this in the spreadsheet as well. Notice that the spreadsheet in Figure 1 allows the analyst to say that five people indicated their dentist was influential—that is a number you can report, but the spreadsheet also records how the remark was made and by whom. Notice that it allows one person to give more than one answer. From a spreadsheet like this one could prepare a written report of the results.

Figure 1—Example of focus group results output [9]

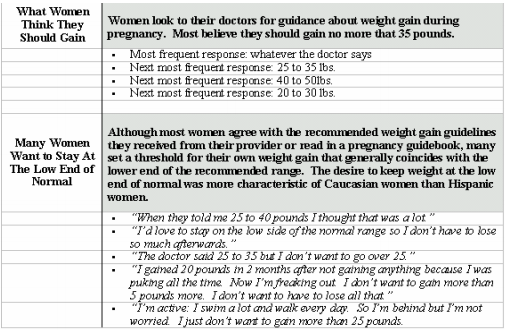

How might the results look in a written document? Figure 2 gives an example below, and concerns the question of how much weight women believe they should gain while they are present. Here the analyst records the most common response, as well as a breakdown of the range of responses given.

Figure 2—Example of focus group results output [9]

Step 4—Reporting. A written summary of the results will be delivered to the client, and while they will want a full report that might go to 100 pages, they will definitely want a very succinct description as well, and easy to read tables or charts. Always remember that the people who make the most decisions will be working with the least amount of information, so the quality of the information they receive must be high. In the results you should describe the themes that appeared in the focus group answers, including the frequency of the themes, the range of themes mentioned, how themes differed across demographics, and any other information the client might find useful.

Video 11—Brief video on analyzing focus group data

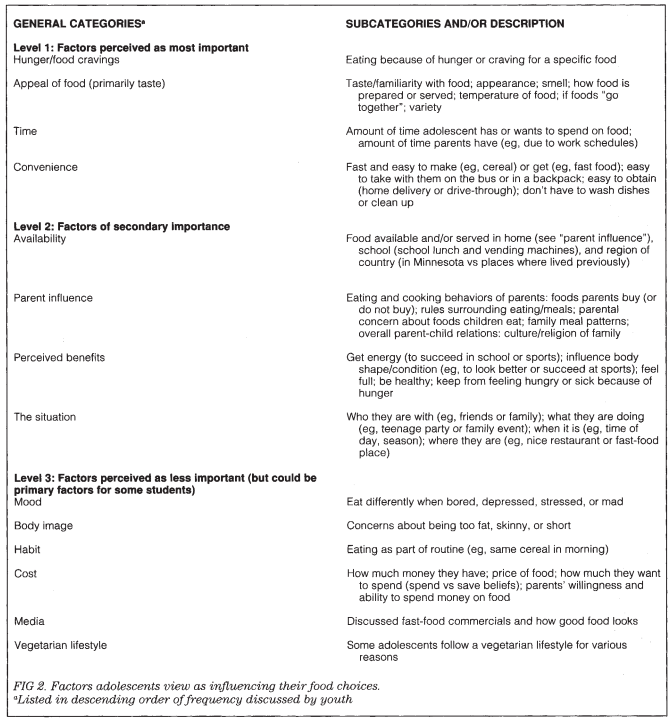

An example of output from a published study is shown in Figure 3, where adolescents were asked about the factors influencing their food choices. This Figure shows the general themes mentioned, a organizes them an an intuitively appealing way. The bottom of the figure shows that the most commonly cited answers were listed first, so adolescents consider things like taste and convenience ahead of parental influence, and parental influence ahead of media. The figure is nice because it not only shows the individuals’s answers to the questions, but which answers were given most frequently, as well as further descriptions on how the theme was described.

Figure 3—Example of focus group results output [10]

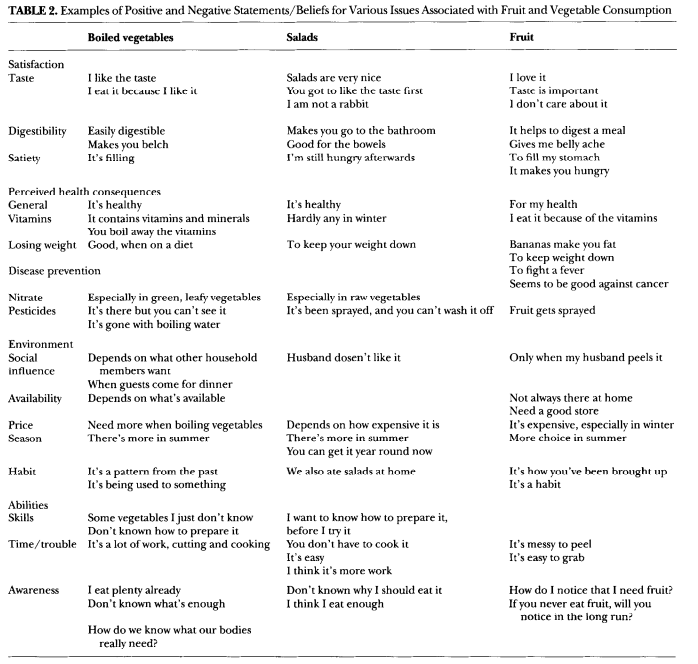

In a focus group on the determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption the figure below gives different results for different categories of food and stylized descriptions of the answers. In this one figure one can get a pretty good idea of what people said in the groups, and sometimes the client is not as interested in the most frequent responses as they are a succinct description of all the responses.

Figure 4—Example of focus group results output [11]

Other Sources

Focus-group interview and data analysis. [12]

Guidelines for conducting a focus group, by Eliot and Associates. [9]

Designing and conducting focus group interviews by Richard Krueger at the University of Minnesota.

References

(1) Curry, Leslie. June 23, 2015. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods: Focus Groups (Module 4). Yale University. Accessed August 2, 2016 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCAPz14yjd4.

(2) Morgan, David L. 1996. "Focus Groups." Annual Review of Sociology. 22:129-152.

(3) Ziv, Stav. April 29, 2015. "Advertising Professors Assess the Bud Light Fiasco." Newsweek. Accessed August 2, 2016 at http://www.newsweek.com/three-advertising-professors-bud-light-fiasco-326830.

(4) Davenport, Ken. November 10, 2014. "10 Things I Learned From Broadway TheaterGoers at My Focus Groups." The Producer’s Perspective. Accessed August 2, 2016 at https://www.theproducersperspective.com/my_weblog/2014/11/10-things-i-learned-from-broadway-theatergoers-at-my-focus-group.html.

(5) Bellington Public Schools. October 2015. Food Services Focus Group Analysis. Accessed August 2, 2016 at https://bellinghamschools.org/sites/default/files/Focus%20Groups%20Report.pdf.

(6) Coleman, Holly Holbrook. 2007. "Focus Groups on Consumer Attitudes on Food Safety Educational Materials in Kentucky." University of Kentucky Master’s Theses. Paper 471. Accessed August 8, 2016 at http://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/471.

(7) Nielson, Jakob. January 1, 1998. Estimated Cost of Running a Focus Group [web article]. Nielson Normal Group. Accessed August 3, 2016 at https://www.nngroup.com/articles/focus-group-cost/.

(8) Greenbaum, Thomas L. 1988. The Practical Handbook and Guide to Focus Group Research. Lexington Books: Lexington, MA.

(9) Eliot and Associates. 2005. Guidelines for conducting a focus group, by Eliot and Associates. Accessed August 10, 2016 at https://assessment.trinity.duke.edu/documents/How_to_Conduct_a_Focus_Group.pdf.

(10) Neumark-Sztainer, Dianne, Mary Story, Cheryl Perry, and Anne Casey. August 1999. "Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: Findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents." Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 99(8):929-937.

(11) Brug, Johannes, Sigrid Debie, Patricia van Assema, and Wies Weijts. 1995. "Psychological Determinants of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Adults: Results of Focus Group Interviews." Food Quality and Preference. 6:99-107.

(12) Rabiee, Fatemeh. 2004. "Focus-group interview and data analysis." Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 63:655-660. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004399.